National Profile: Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.)

The Soviet legacy was a complicated one for Mission Survivors. To Americans, Anglophone Canadians, a majority of Britons and Eastern Europeans, the Portuguese, African whites, the Iranian elite, Bolivians, Yugoslavs, Afghans, Greeks, Filipinos, Australians, and about half of Scandinavians, Soviet Communism was best described by President Ronald Reagan: "Life as it could be, not as it should be, Mr. Ustinov."

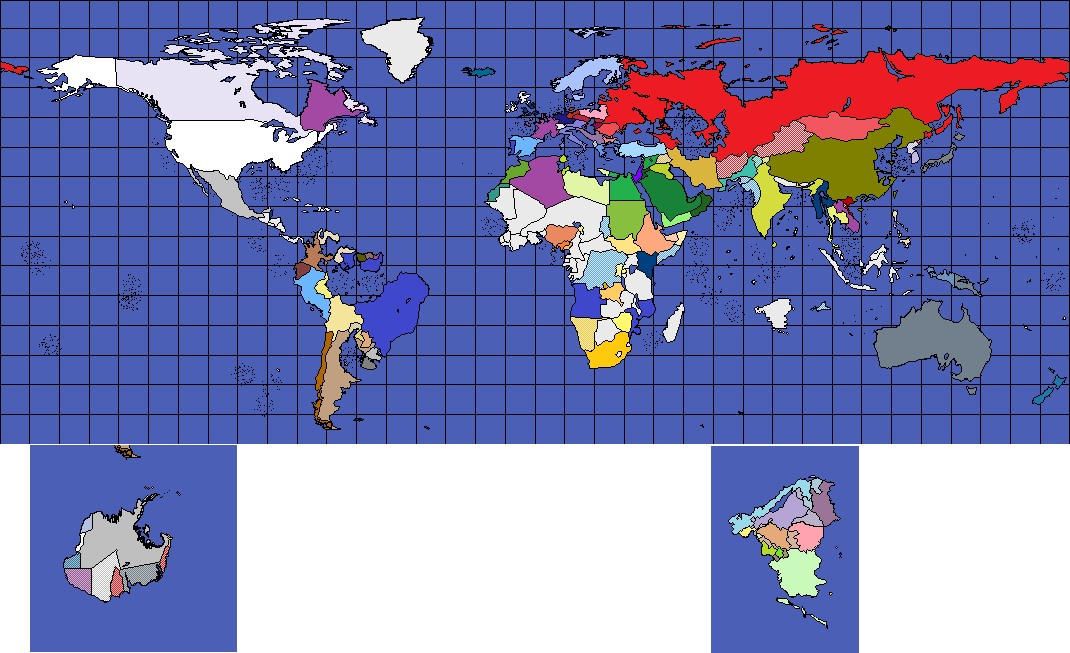

There was truth, of course, to these concerns. Soviet citizens were the property of the state. There were no freedom of the press, no freedom of movement, and only a sad simulacrum of free enterprise beginning in the 1980s. Particulars prohibitions might change at the margins, allowing for self-expression or retroactive critique of past leadership, but the labor camps were once again full in 1980 and remained that way until the 2020s. There were a dozen Soviet satellite states, and little effort wasted on pretending that orders were not passed down daily from Moscow. East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Mongolia, Qwin, and Koryo were only rarely out-of-step with the Soviet march. The special plight of the Afghan peoples, driven from their homes, their children maimed by landmines, was rarely out of the American press.

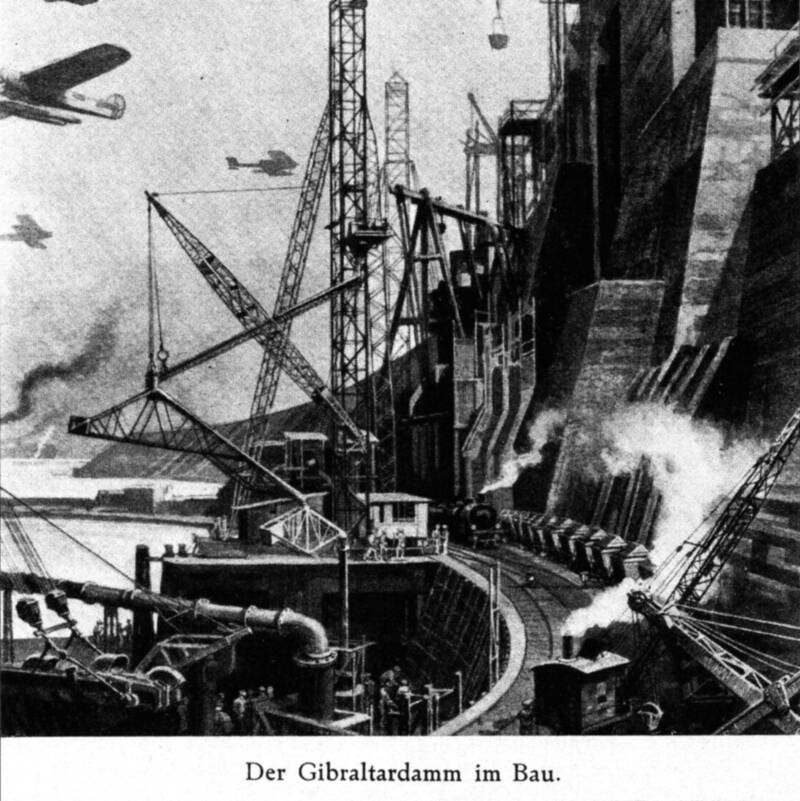

Yet the Soviet Union was indisputably a superpower. Russian standards of living rose sharply during the later half of the twentieth century, especially in the largest cities. By 1980, the average lifespan of a Soviet citizen was seventy years--up from forty in 1917. Soviet education produced world-class physicists, chemists, biologists, mathematicians, engineers, geologists, and computer scientists. The Soviets led the way into space and achieved numerous firsts: first orbital launch vehicle (1957), first satellite in orbit (1957), first person in space (1961), and first person on the Moon (1969). Other Soviet inventions included the programmable computer (1950), the nuclear power plant (at Obninsk in 1954), the hologram (1962), and the personal computer (1965). Soviet medicine was known to be well advanced in the areas of aerosol vaccination, organ transplant, and the humane treatment of psychiatric conditions. The Soviet navy actively participated in arctic and antarctic research. Aeroflot operated the world's largest fleet of commercial supersonic passenger aircraft and, from 1982, carried all space traffic sunward and back by special agreement with the United Nations, over the strenuous objection of Comprehensive Transport and the United States of America. In 1994, the U.N. adopted Soviet principles of construction for mid-ocean rigs as a global standard. Soviet automobiles and farm machinery were ubiquitous features of modernity in Second and Third World countries. Soviet assistance was indispensable to infrastructure megaprojects like Egypt's Aswan Dam, Cuba's Juragua Nuclear Power Plant, the Sunda Strait Bridge, Ethiopia's Renaissance Dam, reconstruction of the former Dutch space elevator at Jakarta, and the Lake Baikal Diversion that watered most of northern Mongolia.

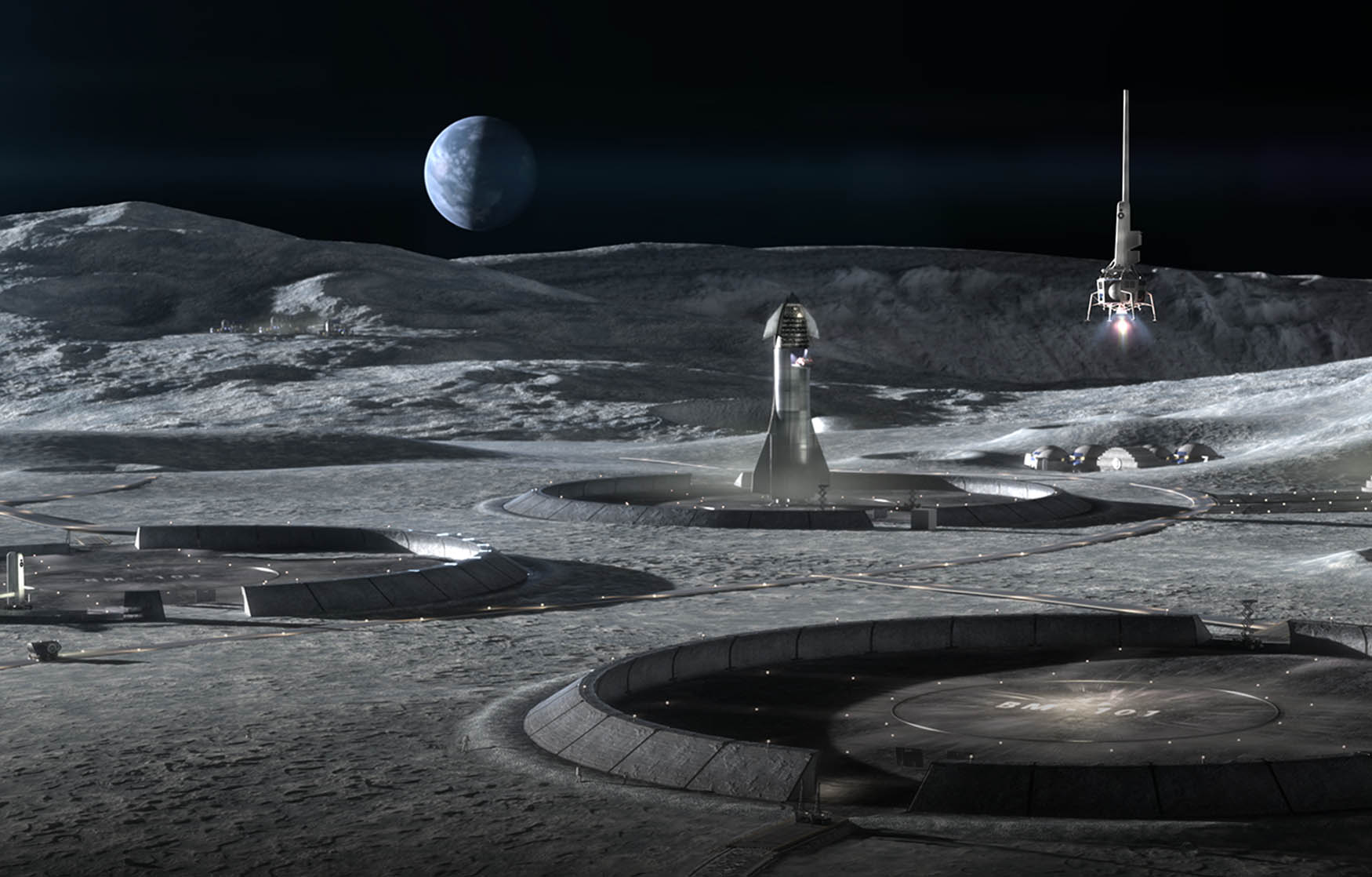

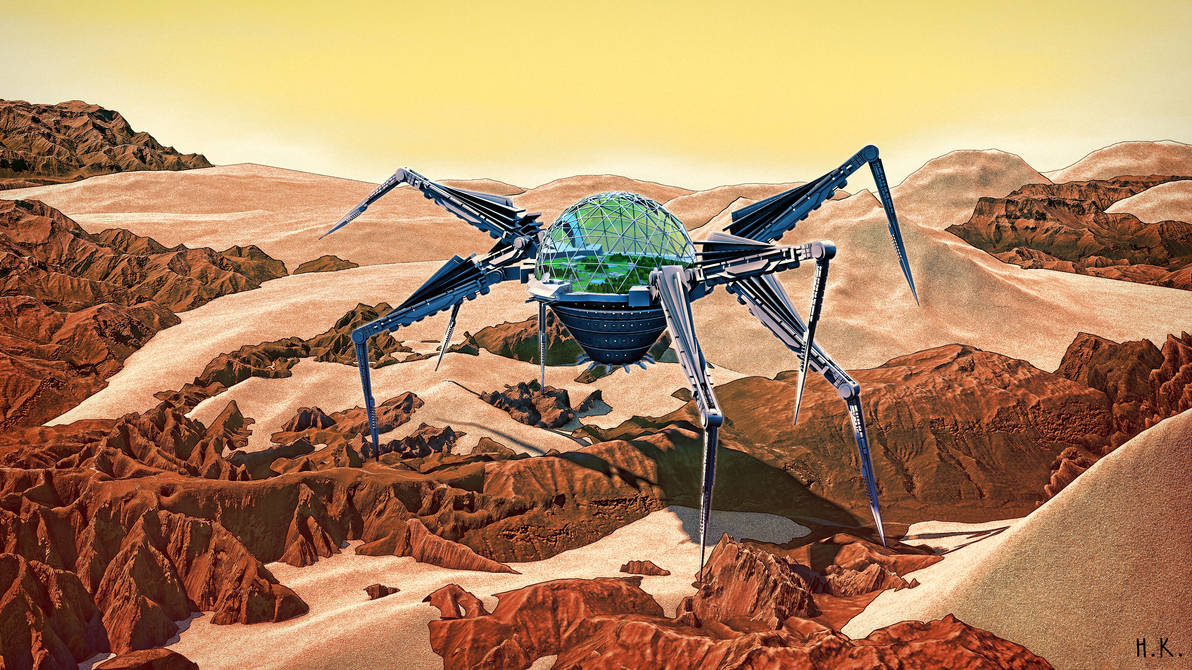

The Soviet moon landing of June 26, 1969.

Among Arabs, Frenchmen, almost half of West Germans, for an overwhelming number of Africans, and in India, "the Russians" were treated with hopeful caution. Anyone not warm in the American embrace or held fast beneath a European thumb could rest assured that the Soviets would take an interest. They would listen. Advocate in the world's great multilateral forums. Remonstrate, perhaps, with the Americans or the Europeans. And when the time came, the Soviets would live up to their words--with generous subsidies of arms and men. The French, the Indians, and to a lesser extent the free Baltic states, learned to play the Soviets at their own game. "The French Proxy" entered Western lexicon as any vote or initiative in the U.N. out of character for the caster but advantageous to Russia. It was an open secret that French and Indian firms resold Western technology to the Soviet Union, especially electronics. Embarrassed by the politics of the decades-long Afghan debacle, the Soviets touted instead their popularity in Xinjiang, where they were greeted as liberators by the oppressed Uyghur majority in 2017. Strong Soviet allies included Cuba (before 2050), Ethiopia, Nigeria, North Vietnam, India, and Indonesia.

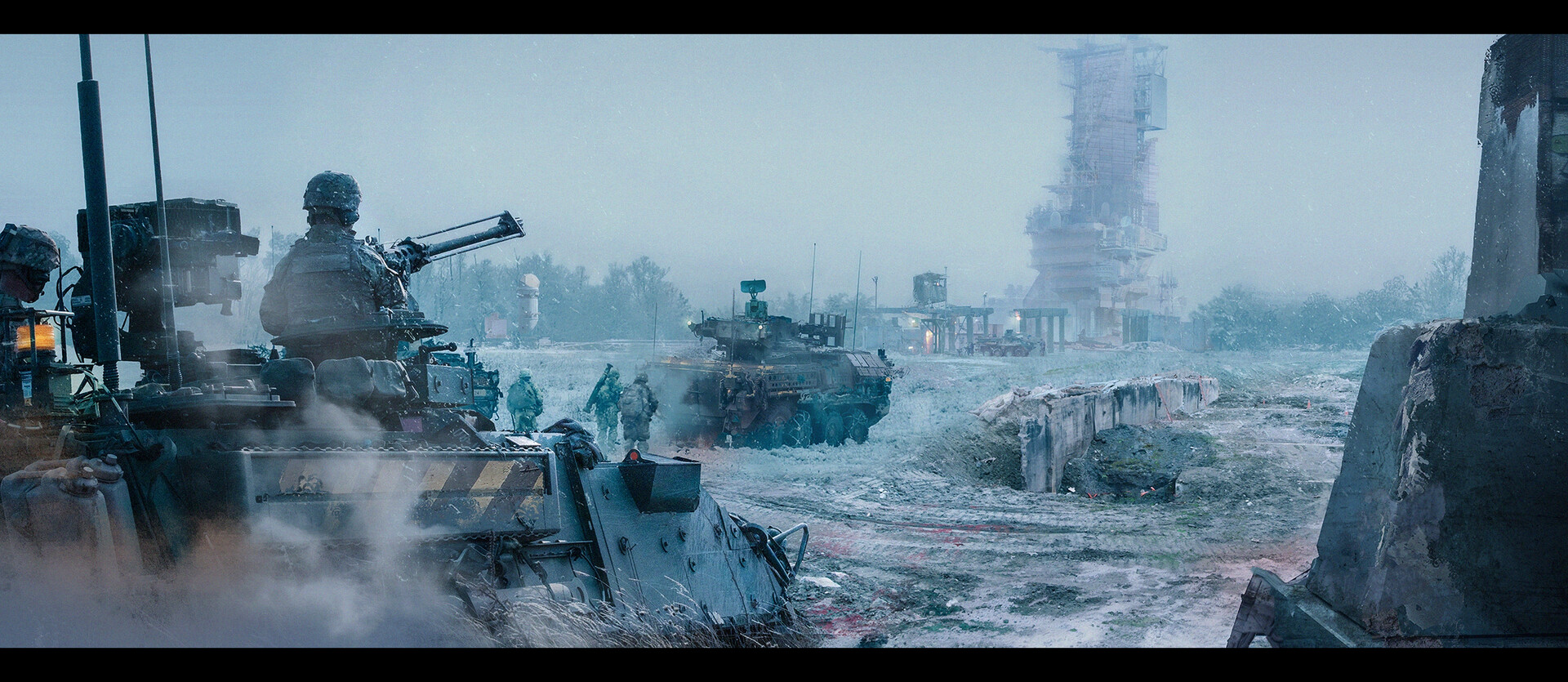

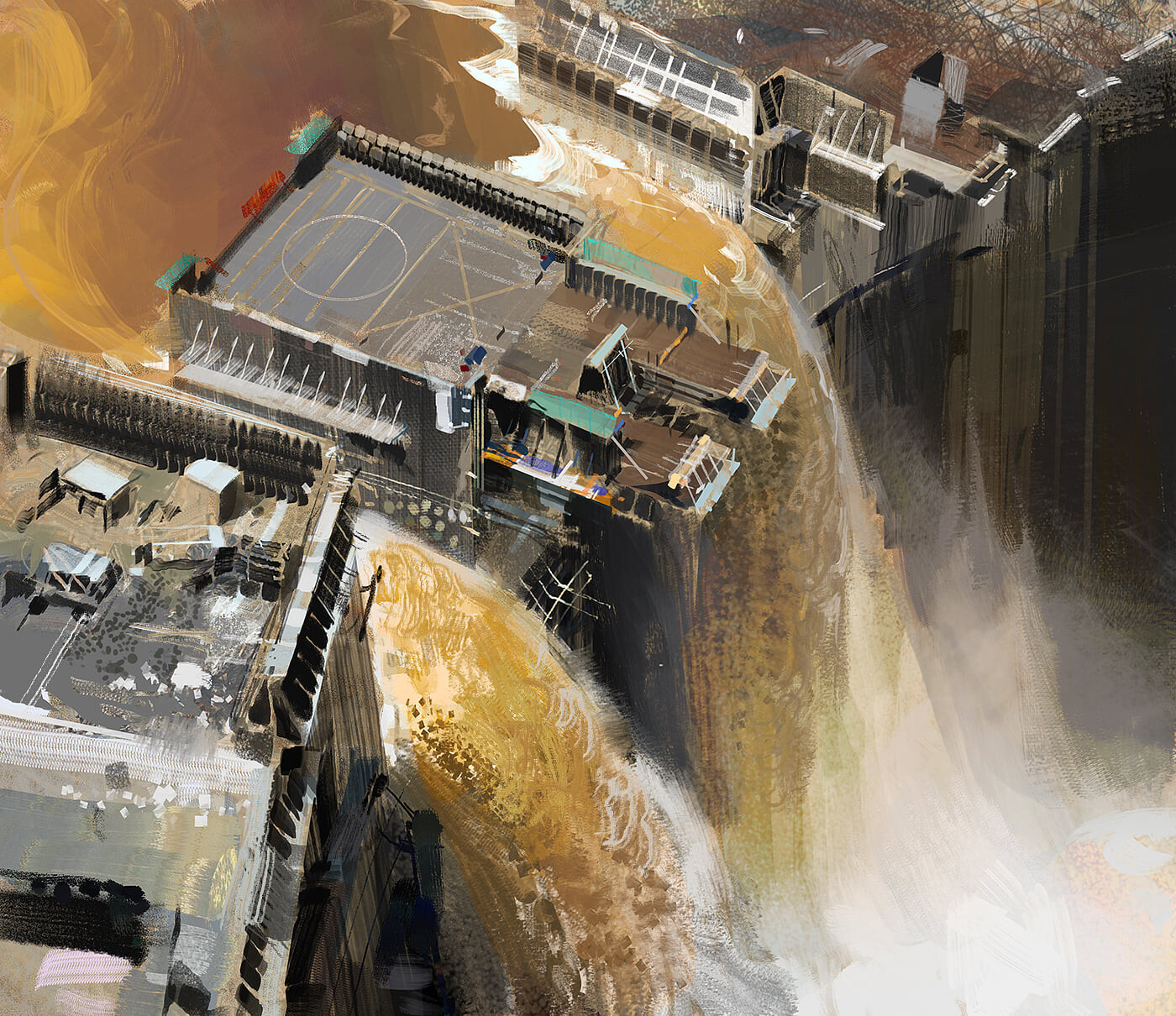

Snow falls early in East Berlin in September 2062. Traffic along the Old Wall is light.

The Soviets were active humanitarians, making the largest per-capita commitment to recovery operations in the Indus Valley Exclusion Zone among all contributing nations. Soviet hydrologists played a major role in earthquake and tsunami response in Turkey, Syria, India, Japan, Israel, Lebanon, and the IOEZ.

Soviet tractor used to string cable car line in the foothills of the Himalayas to assist with the relocation of industry from the IVEZ. Later resold to Gath for work on the Sapphire Railway, a rack-and-pinion railway used to climb the Saggrinid Mountain Range. The inheritors named their craft "Tyrannus" in a pun on popular criticisms of their king.

Western scholarship has coalesced around the idea that there have been two phases of Soviet foreign policy: a Timid Phase shaped by American boldness during the short window of its nuclear supremacy in the 1940s and early 1950s, and a Muscular Phase beginning with the Sino-Soviet Clash of 1969 that reached its maximum expression with the Christmas invasion of Afghanistan ten years later.

Soviet war planners were caught off-guard by the American escalation to atomic warfare in Korea, and it caused them to throttle back on actions that might have been considered provocative to Washington. Although the primary human costs were felt by the Chinese and North Koreans, the Soviets contented themselves with seizing a small buffer zone to protect Vladivostok before pressing Beijing to negotiate. A final accord was reached in February 1952, leaving the South Koreans in control of a mostly unified but utterly wrecked peninsula. The American public hailed the war as a great victory and wondered what else the Bomb could do for them, seemingly oblivious to the fact that Korean recovery cost them more in blood and treasure over the next twenty years than Korean defense had in less than three. Just two years later, the Americans let the French use four small atomic bombs in Indochina, underlining the mortal danger to any power that could not reply in kind.

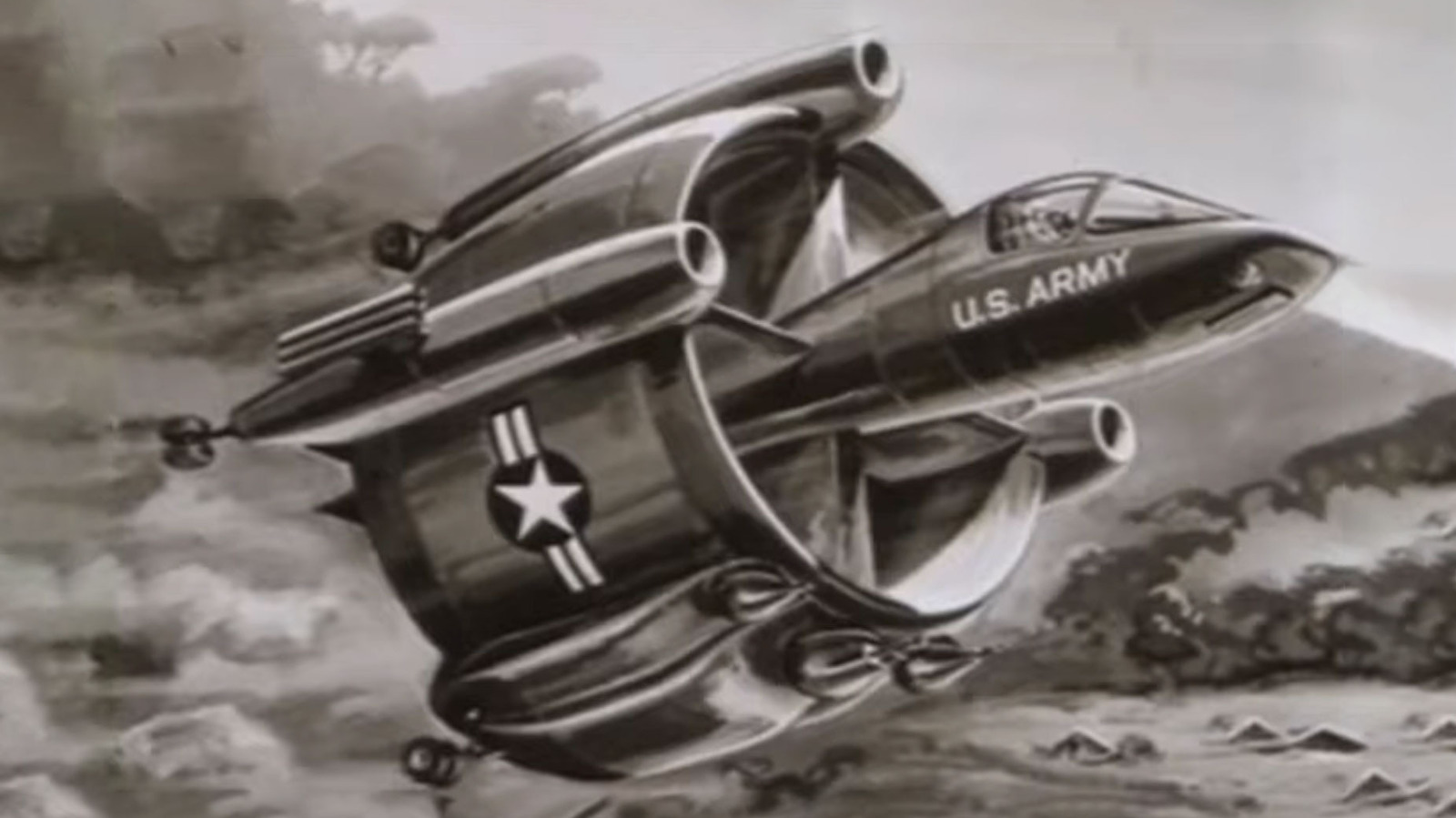

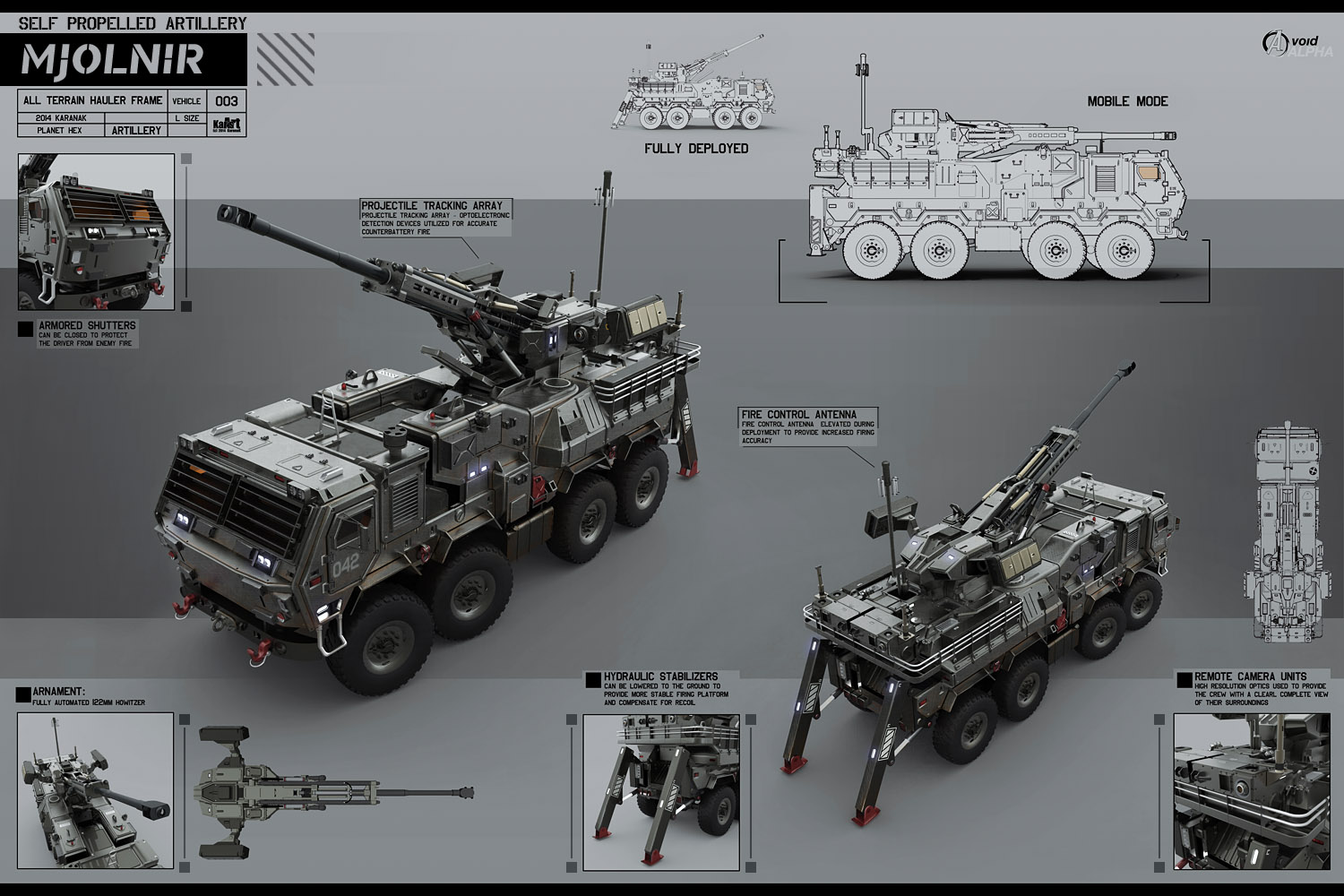

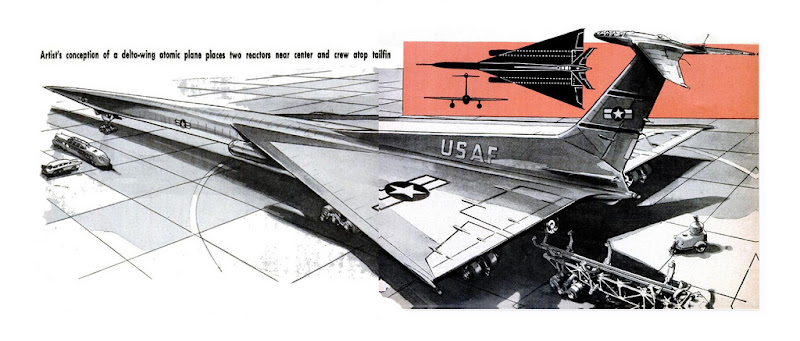

Soviet leadership was spooked. Huge new investments were made hardening the U.S.S.R.'s strategic rocket forces and increasing both rail-based launch systems and ultra-long-range bombers. Despite local superiority of conventional

and

nuclear forces in Europe by 1960, the Soviets remained concerned about American unpredictability. When the Americans agreed to remove PGM-19 Jupiter missiles from Turkey in return for removal of Soviet missiles in Cuba in October 1962, the Politburo felt the two powers had come to something of an informal understanding--a tit-for-tat relationship in which saber-rattling had no place. They tried diplomacy instead, toning down their bellicosity almost to the point of obsequiousness, even ceasing material support for independence movements working against the French, hoping to widen the growing rift between the United States and its European allies over the Suez Crisis. The strategy paid some dividends in 1966 when the French withdrew entirely from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, although critics charged that the Soviets had missed huge opportunities to influence the direction of post-liberation politics in Africa. The wooing of France became a blueprint for future Soviet adjustments of the international order. (Similar overtures to Portugal were less successful, and the Soviets persisted in supporting both the MPLA and FRELIMO into the new century.) Threats of military force were more useful against those too weak to resist: a mid-decade build-up of forces on the Finnish border dissuaded the new Scandinavian Union from affiliating with NATO altogether, and wrong-footed the Dutch in Indonesia, eventually dooming their attempts to preserve a colony there.

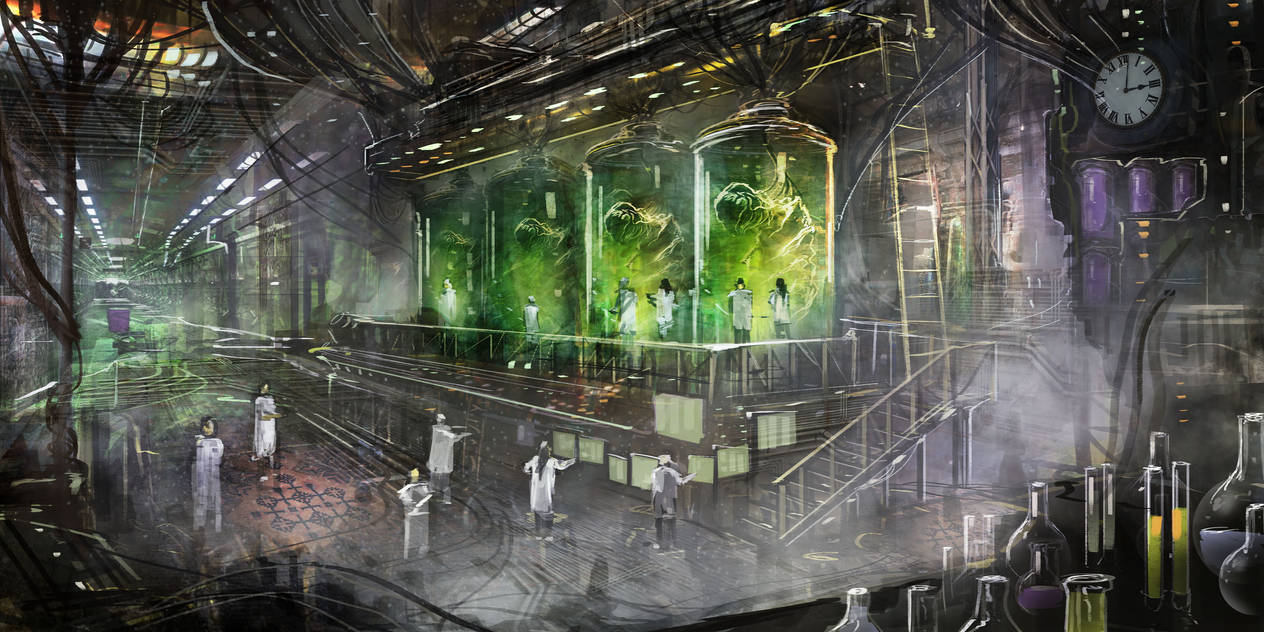

Then came disaster. For most of 1969, the Soviet Union and China were at war in northern Manchuria. From that point forward, Soviet attentions shifted decisively eastward. The Fulda Gap remained a convenient political pressure point, and Moscow continued to recognize the United States as its primary competitor for global influence, but Soviet forces expected, and prepared, to fight against a numerically superior enemy on a front spanning more than 5,000km. China was the more urgent threat. By 1974, growing desperate, the Soviets added a new tool to their arsenal: the All-Union Science Production Association Biopreparat, which would give rise to the world's largest and most dangerous bio-warfare program.

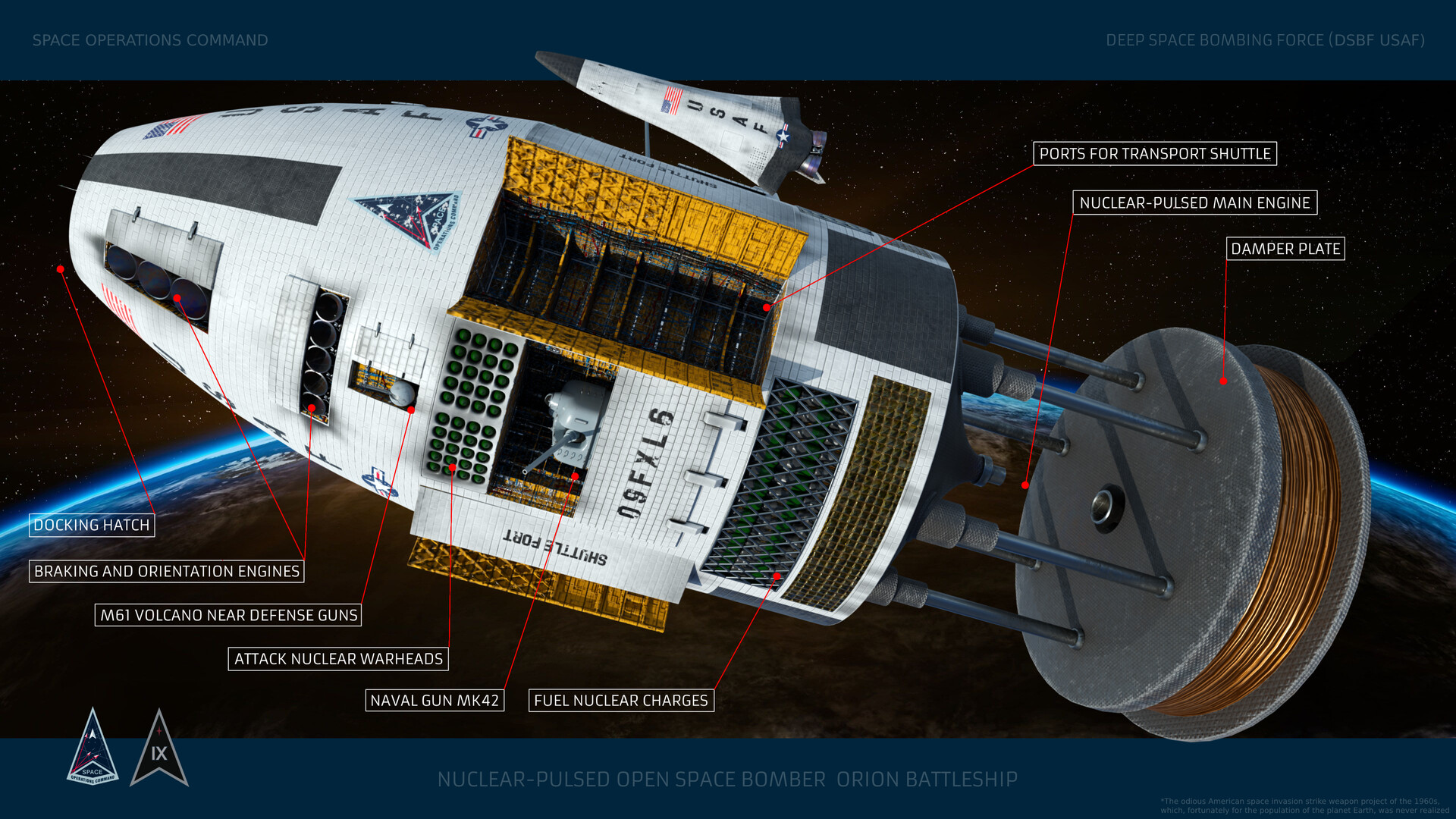

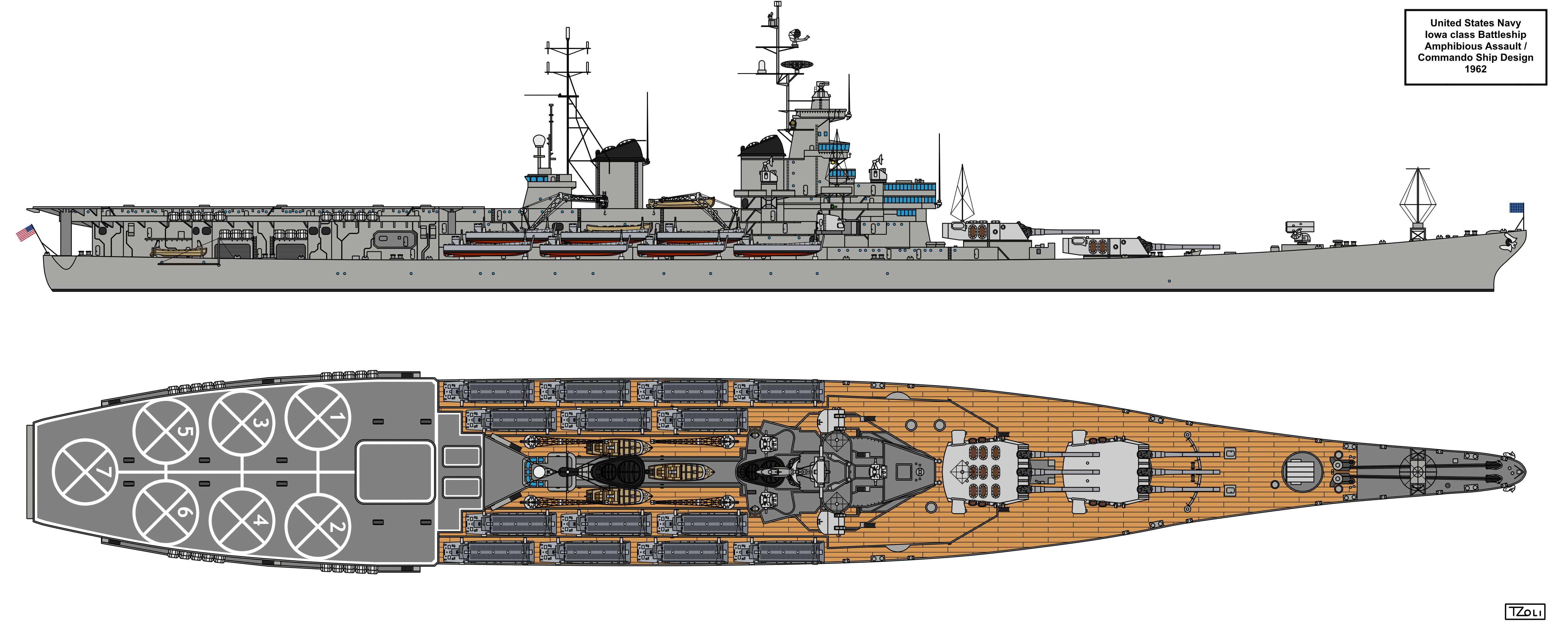

Soviet space efforts, code-named "Firebird," meanwhile lost ground during the 1970s as the geopolitical storm clouds gathered. To compensate, the Soviets tried sabotage. There were several clashes between American and Soviet moon men. Each side accused the other of provocation, but the Soviets got the better of most of the fights, which later records confirmed were pursued at Moscow's instigation. It did little good. The U.S. Marines were authorized to add 2,000 "space commandos" to their ranks. In 1980, the Americans built the first permanent colony on the Moon, taking back the initiative in the Space Race. The U.S.S.

Orion

, a space-borne warship, went up that same banner year and finished trials in '85. The new American president, Ronald Reagan, terrified the Politburo, and they readily believed his assurances to the world media that

Orion

could shoot down ICBMs in-flight.

Enter new Soviet Premier Marat Barrikad, who had spent time in the United States and thought himself a keener judge of the American psyche than most of his contemporaries. Barrikad believed that as American military superiority increased relative to the Soviet war machine, a countervailing soothing effect would result. They would come to see themselves as invulnerable, and the Soviets as an unworthy opponent who no longer demanded a forceful response. Democratic Party opponents were already criticizing Reagan as a cowboy, and even fellow Republicans worried over the runaway costs of his defense build-up. This gave the Soviets options. Barrikad dialed up support for liberation movements in Southern Africa, where white minority governments and colonial regimes were fighting a rear-guard action against Western public opinion. Soviet infusions of money, advisers, and equipment were carried out through Cuban, Yugoslav, and East German clients, and timed for peaks in the cycles of mutual alienation between Portugal and the State Department.

With nuclear power flowing freely in the United States, Barrikad also saw his moment in the Middle East. The Soviets rebuilt the armies of the Syrian-Arab Republic and egged them on against the Israelis (an over-calculation that cost Jordan a fifth of its national territory, culminated in the 1981 assassination of Anwar Sadat, and, paradoxically, reinforced the growing American conviction that the Soviets were second-rate competitors). After learning that the Shah was sick with cancer in 1978, Barrikad accelerated support for Iraq. Reasoning that China was more afraid of the Soviets than the Soviets of China, Barrikad reopened diplomacy with Beijing, securing a long period of deescalation. He welcomed Indonesian independence as a Communist state, ignoring the ill-fated rump in Dutch New Guinea, and, in 1991, hacked Italy from NATO through support for a successful Socialist majority in that country's parliament.

The Soviet's worst blunder came in the late 1980s, when Barrikad tested American resolve by passing a low-yield nuclear warhead to the Iraqis for use against Iran. The backlash was swift and overwhelming: the Iranian military swept across Iraq's northern tier to effect the secession of Kurdistan while the Americans quickly and correctly traced the offending isotope back to its source.

While Barrikad drew down funding for subsequent Soviet moon landings and imposed delays on the country's answer to

Orion

(less an expression of doubt than to avoid economic overheating), he pushed for greater action in the Inner Solar System, and is usually acknowledged as the major influence responsible for the Soviet grip on activity above Mercury and Venus. These latter footholds proved to be a saving grace for the Soviet economy. When Barrikad died in 1992, he was succeeded by Mikhail Gorbachev, whose name is now synonymous with political and economic liberalization. To achieve

his

vision, Gorbachev forged close relations with fellow leaders in France, Italy, Turkey, and India, often cooperating on industrial and research projects to spread costs.

The twenty-first century for the U.S.S.R. was dominated by five themes: discovery and interaction with the Mercury vulcanoids, renewed conflict with China and the United States, environmental catastrophe, interference in the IOEZ, and post-liberalization criminal activity.

In 1982, Soviet probes discovered the hypothesized vulcanoid objects inside Mercury's gravity well, some of which contained new elements, including Barrikadium-109. The hard currency earned from strip-mining these asteroids in the early 2000s helped keep the Soviets afloat through the disruptive "shock therapy" of exposure to the free market under Gorbachev and the "snap back" that followed when the hardliners returned to power six years later. The Soviets did make important contributions to the settlement of Mars and the exploration of Titan but otherwise kept their focus sunwards. The Soviet space program was always bedeviled by the lack of access to a friendly space elevator, and benefited considerably after the Indonesian Revolution from the restoration of the elevator built by the Dutch at Batavia, renamed Jakarta.

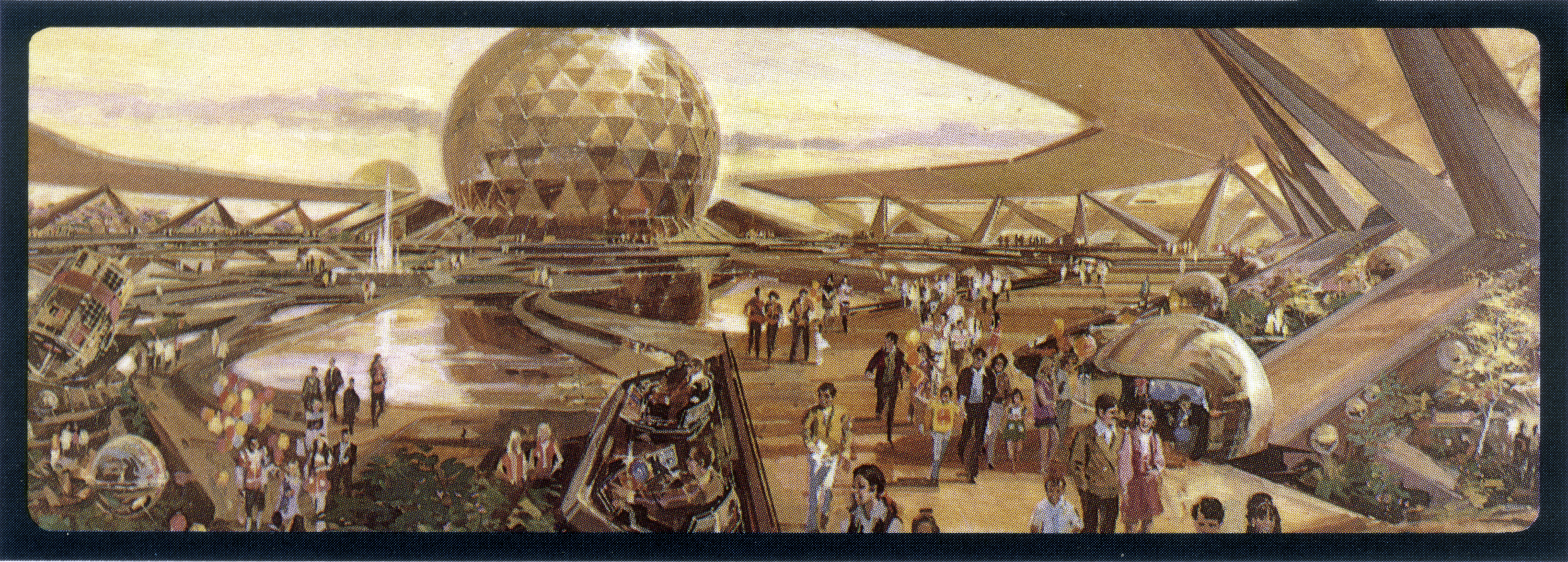

Denezhnaya Kul'tura (Денежная культура) gave Soviet bureaucracy an overlay of glamor designed to impress foreign audiences more at home in New York and Tokyo.

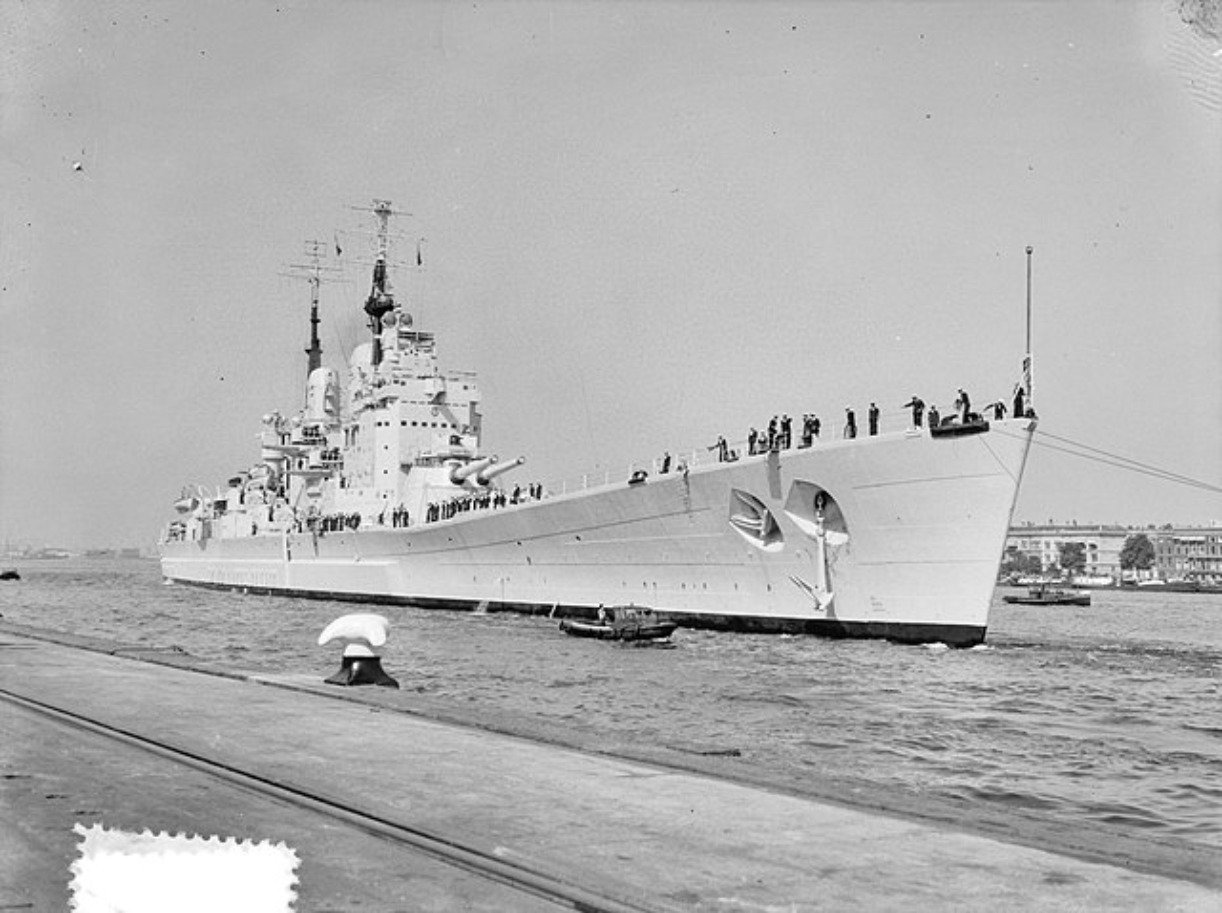

By 2017, the Russians had reached the point of defensive alliance with India. Pakistan hastened into a similar arrangement with China, which increasingly worried about the breakdown of civil order in the nuclear blast zones created during the 1991 Six Minute War. In March 2017, the Pakistani government was facing crisis. Popular unrest in Dacca was overwhelming civil authorities. India was threatening intervention on humanitarian grounds. At the invitation of the Pakistanis, China invaded Arunachal Pradesh. The Chinese calculus was three-fold. First, the Chinese Politburo hoped to signal to India that it would not tolerate intervention in favor of Mukti Bahini guerillas in East Pakistan. Second, Chinese leaders believed the gains they would make could be traded away during subsequent negotiations for favorable concessions in northwest India. Third, Chinese leaders wanted better intelligence on the quality of the Indian Armed Forces since the nuclear holocaust. The war was a disaster for both Pakistan and China, resulting in Bangladeshi independence and the destruction of most of China's nascent blue-water navy after the sinking of two of its aircraft carriers at the hands of Indo-Soviet task forces. (Quite the feat, since both the Indian and Soviet navies suffered from very poor maintenance practices and Soviet aircraft cruiser

Kremlin

experienced a deadly shipboard fire just hours before the engagement that sank the

Shandong

.) The war ended in 2019 with a Chinese return to prewar borders and powerful Pakistani misgivings about the value of Chinese friendship that pushed them toward the waiting Americans. This was not the optimum result for Moscow, but it did at least review the instructive lesson of 1969 that Soviet arms were not to be trifled with.

The Soviet Union's greatest coup against the United States since the 1970s occurred in Quebec, where the Soviets worked closely with the French and the United Nations to gain the province's independence during the Second American Civil War. Soviet involvement was extensive: Soviet submarines delivered weapons to Felquiste terror cells and Soviet special forces helped inflict serious casualties on the NATO (mostly American and Commonwealth) forces that could be spared to help Canada's small army hunt the terrorists. The Soviets used frequent false-flag attacks to turn public opinion against Ottawa, massacring Francophone civilians and blaming Anglophone "Black Watch" militias. There is scattered evidence to indicate that Soviet troops also entered the United States to leaven state separatists and Holnist forces despite the avowed anti-Communism of those movements; many of the sub-contractors provided by Morgan Industries affiliates were Russian speakers who claimed to come from the Russian Diaspora.

The Soviet Union was an Alpha-class nation--more than ten percent of the country's landmass was claimed by rising sea levels. Only Western Europe and certain Polynesian islands suffered greater calamity. Most nations coped with the change by taking to water. The Soviets in particular preferred land or space, drawing their displaced peoples inward and building large habitats at the L[sub]1[/sub] and L[sub]2[/sub] LaGrange Points. Soviet industry was highly active in what became the badly-polluted intermingling of the Black, Aral, and Caspain Seas. The problem was made considerably worse by the prevalence of industrial disasters, especially nuclear disasters, within the country's borders, which exposed tens of millions to life-altering illness and inflicted severe losses on Soviet agriculture so that the country was often a net importer of food.

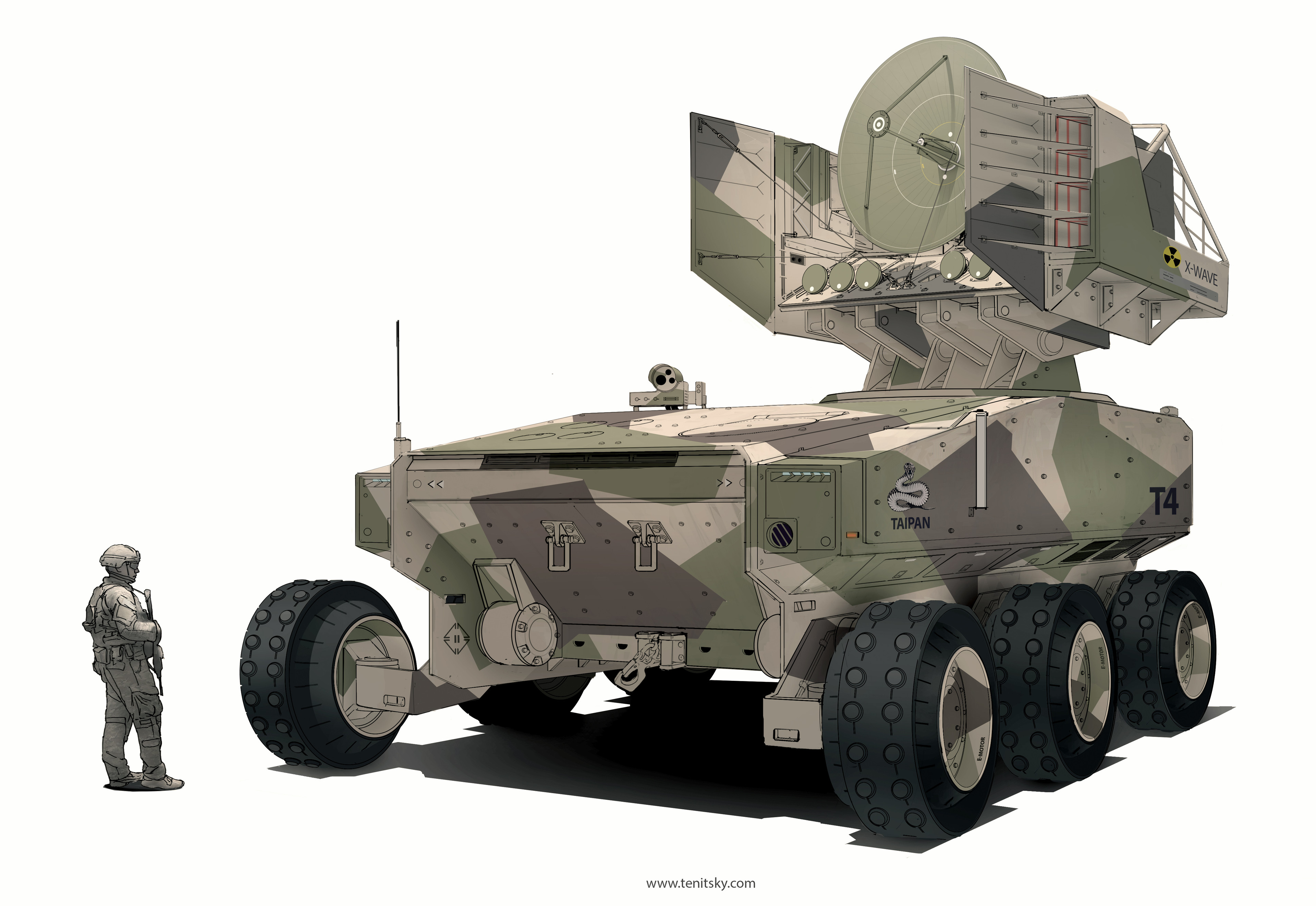

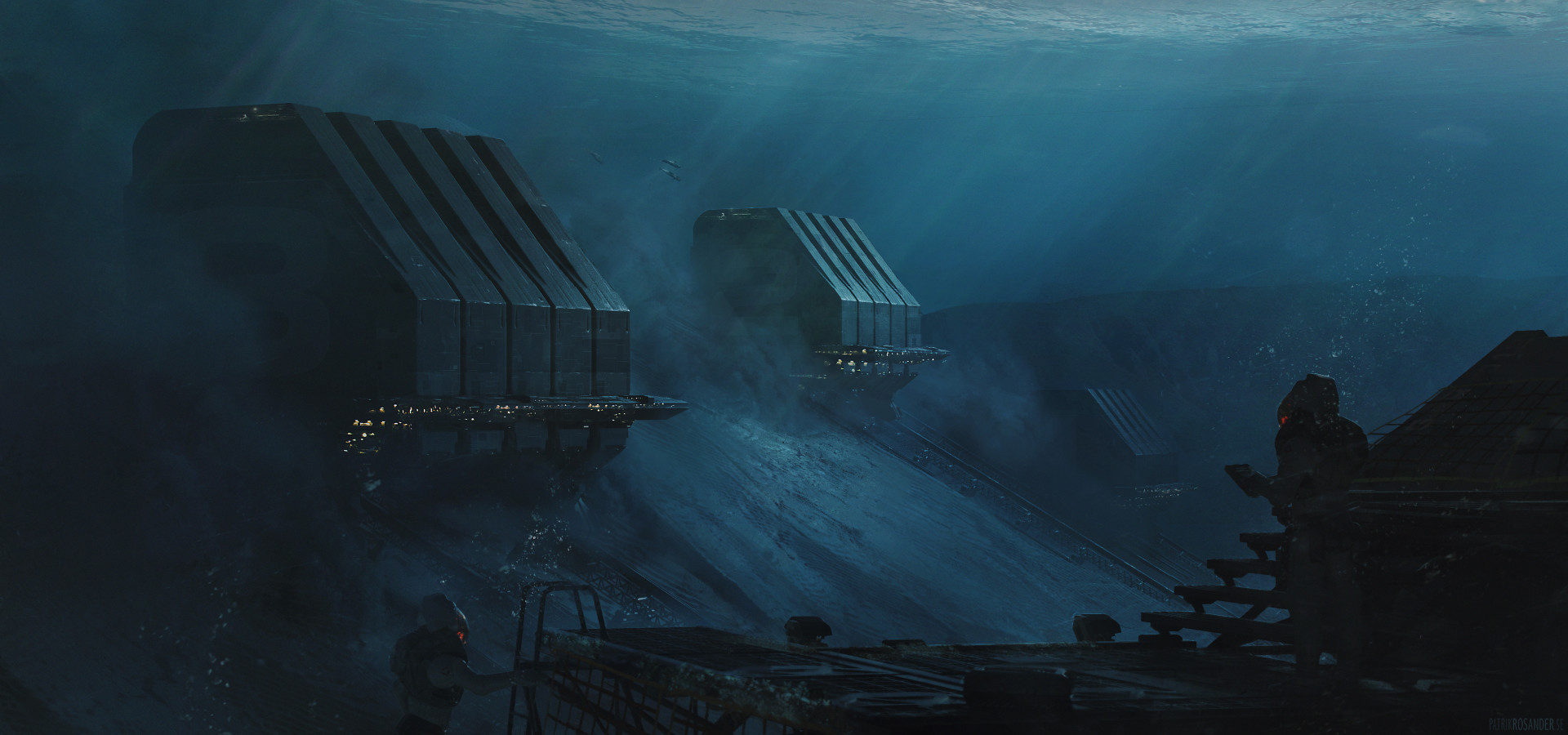

Following the example of Barrikad, later Soviet leaders maintained a large civil and military presence in the IOEZ, where training and cooperation with the Indian Navy helped create the groundwork for successful joint maneuvers during the 2017-19 war. Soviet missions were no different than those carried out by other Great Power interlopers: delivering humanitarian supplies, ferrying evacuees from the path of typhoons, suppressing pirates, and conducting diplomatic visits in support of commercial appeals. The Soviet Navy constructed various artificial islands for its own purposes, including as listening posts.

Criminal activity in the Soviet Union was known to be extensive, providing a living to an estimated eight or nine percent of Soviet citizens. Corruption was widespread due to political disaffection, especially over cronyism. Many officers sold military equipment to supplement their salaries, an acute problem among those deployed to foreign war zones. The Soviet government often used Russian organize crime as a front for intelligence operations.

Sources:

The date and idea for the Russian moon landing are from the television show

For All Mankind

. Source for the moon landing art is unknown.

Quora user Alexander Ginnegan offers a

fascinating list

of Soviet scientific-technological achievements.

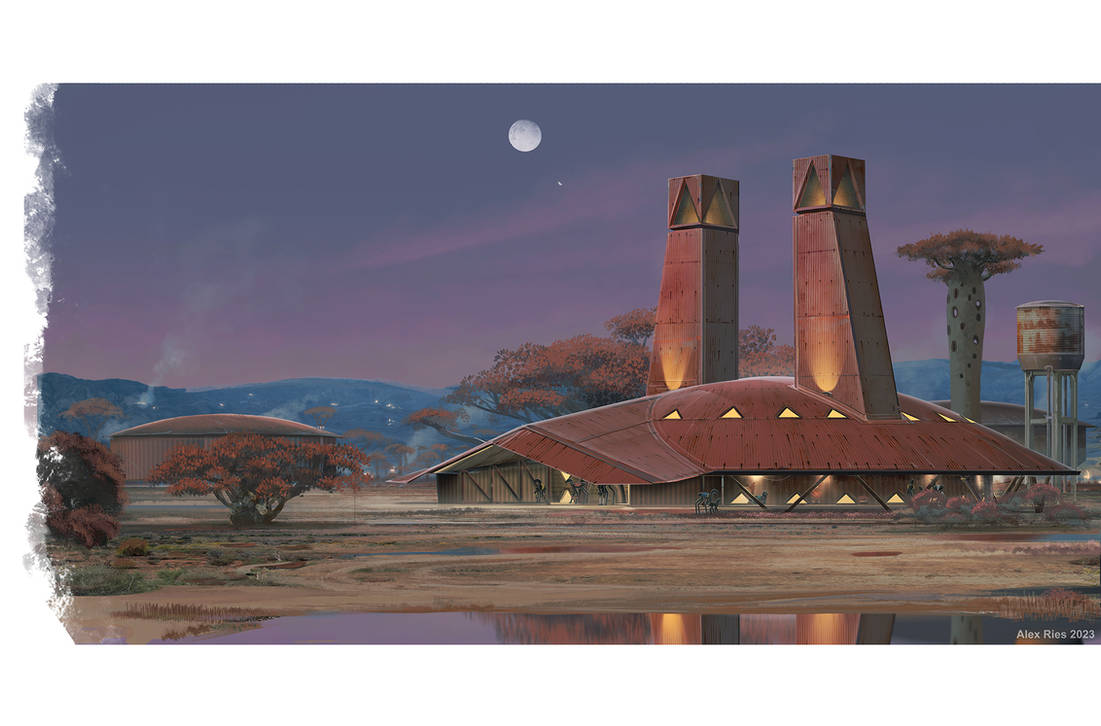

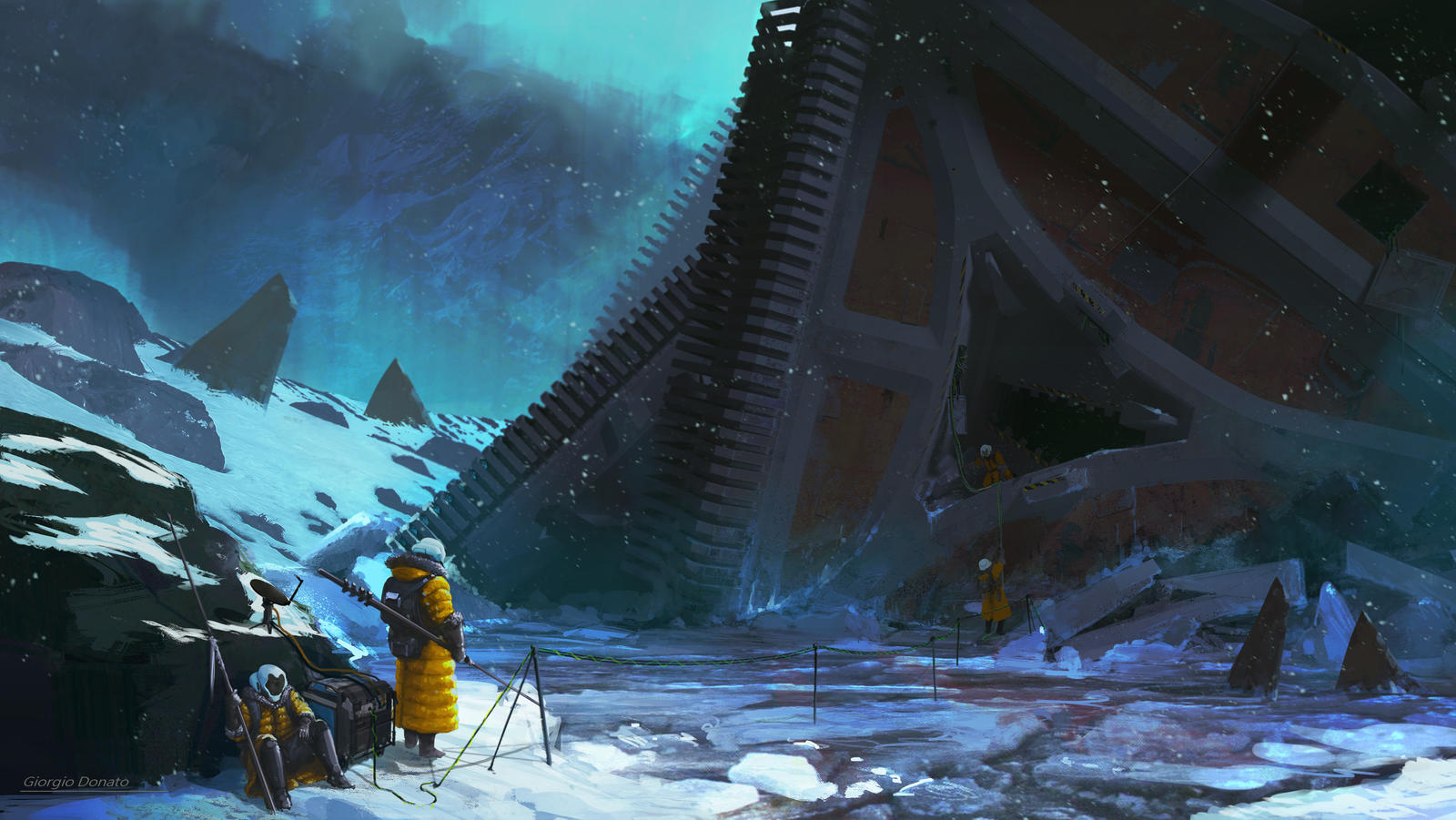

Picture of "East Berlin" is "777Jihad" by isleeyin on DeviantArt.

Picture of tractor is "Steam Crawler" by kceg on DeviantArt.

Picture of futuristic Moscow is "USSR 2.0" by ianllanas on DeviantArt.

The Quebec Independence War concept of false-flag attacks by a "Black Watch" unit is from

Cold War Hot

, ed. Peter G. Tsouras.

.jpg?1420687878)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/3JC24YVHCVENDAQFF74ZQPVWFU.png)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(644x219:646x221)/03-Stockard-Channing-6fcd63e66d0b4a928d9f3a0ff891c1ef.jpg)